Books

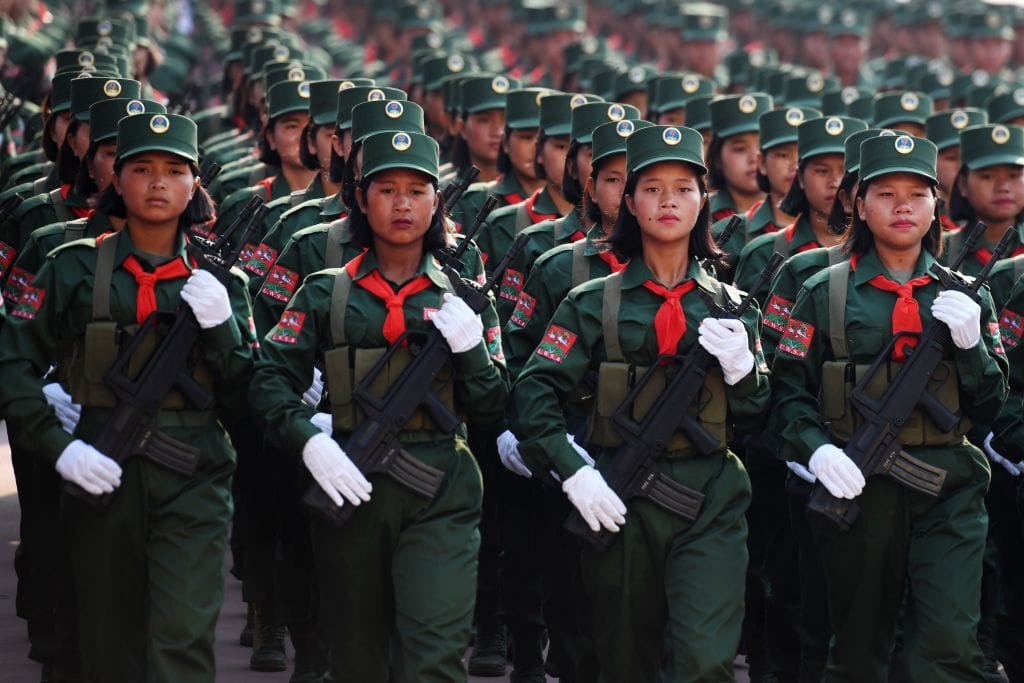

Members of the United Wa State Army. Ye Aung Thu/AFP/Getty

The Asian republic run by a druglord

In the remote border mountains between Myanmar and China lies a little-known “narcotopia”, says Jake Kerridge in The Daily Telegraph. Blessed with “cold mountain soil” perfect for growing opium poppies, the Wa highlanders have spent the past half-century manufacturing heroin on an industrial scale. In 1989, they founded their own autonomous region, Wa State, which now covers around 12,000 square miles – roughly the size of the Netherlands. This “forbidden republic hiding in plain sight” sits at the core of the Southeast Asian drug trade. It generates an astonishing $60bn a year from methamphetamine alone, money that funds a “well-equipped army” to defend Wa against its neighbours. Behind the state’s prosperity lies “treasurer-in-chief” Wei Xuegang. A logistical genius who masterminded strategies for shipping heroin to America, Wei is perhaps “the most successful drug lord of the 21st century”. Not that he courts publicity. He is a “renowned germaphobe” who has lived for years as a recluse in a mansion guarded by a hundreds-strong “praetorian guard”.

The irony is that Wei’s cartel “could never have come into existence” without the CIA. In the 1960s and 1970s, the agency was prepared to aid “virtually anyone hostile to communism” – so they smoothed the way for the Wa people and other mountain-dwellers to export drugs to Thailand, in exchange for intelligence on their Chinese neighbours. As Patrick Winn describes in his terrific new book, this led to scenes that sound like they’re straight from a Joseph Heller satire. At times, for example, US Drug Enforcement Agency operatives who had been authorised by Richard Nixon to “smash the drugs trade” found themselves subjected to “veiled threats from mystery men” – who turned out to be CIA agents trying to cultivate the cartels.

Narcotopia by Patrick Winn is available to buy here.

Property

THE COUNTRY HOUSE This 16th-century manor in Norfolk retains an array of period features including mullioned windows, exposed beams and an inglenook fireplace. The eight-bedroom residence also comes with a billiards room, extensive grounds and a timber-framed conservatory complete with a thriving 100-year-old grapevine. Attleborough station is a 10-minute drive, with trains to Liverpool Street in just over two hours. £900,000.

Food

Gastrodiplomat Eva Mendes. Pascal Le Segretain/Getty

The canny tricks of the gastrodiplomats

Governments have long used “gastrodiplomacy”, leveraging their national cuisine to market themselves abroad, says Dan Hong on Substack. The term was coined in 2002, when the Thai government started offering juicy incentives to citizens setting up restaurants overseas: cheap government credit, business support from embassies, and so on. In just under a decade, the number of Thai restaurants abroad rose from around 5,500 to 15,000. Other countries have followed suit. In 2009, South Korea committed $10m of funding for chefs to attend culinary school abroad; in 2011, the Peruvian government launched an internet campaign featuring celebrities such as Al Gore and Eva Mendes endorsing Peruvian food. For countries that lack the “geopolitical influence” of big players in the West, gastrodiplomacy is a canny way of establishing themselves on the international stage.

Less successful are the attempts to control the authenticity of food overseas. In 2006, Japan commissioned a taskforce of so-called “Sushi Police” to assess Japanese restaurants abroad. Secret inspectors were sent to Paris to investigate 80 establishments, a third of which were denounced for “crimes against authenticity” and refused official accreditation by the Japanese government. Last year, Italy announced that only restaurants that used the majority of their ingredients from the homeland would be officially certified as authentic. In truth, few restaurant-goers even know that “authenticity certificates” exist – and “even fewer care”. These efforts sound less like gastrodiplomacy and more like “gastronationalism”.

Enjoying The Knowledge? Click below to share

Nature

“No, stop!” The Ocean Cleanup vessel en route to the GPGP. Ray Chavez/Digital First Media/East Bay Times/Getty

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is “the biggest and by far the most infamous” of all the clumps of rubbish floating in the world’s oceans, says Andrew Kersley in New Scientist. It’s twice the size of Texas and contains at least 79,000 tonnes of plastic. But a plan to start cleaning it up – one project proposes using two ships dragging a 2.2km-long net – may be misguided. For one thing, only an estimated 1% of plastic rubbish dumped into the ocean ends up in garbage patches, so fussing over them overlooks the real problem. And several studies have discovered that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is now “teeming with aquatic life”, including surface-dwelling organisms “ranging from snails to jellyfish”. Three-quarters of all these species are usually at home in coastal waters near land; living on lumps of plastic merely continues their “long history of riding on more natural ocean flotsam”.

Tomorrow’s world

More needed: children playing in Brazil. Getty

It’s getting harder for poor countries to catch up

“Convergence” is the idea that the economic gap between poorer countries and richer ones is narrowing, says Tyler Cowen in Bloomberg. This certainly used to be the case, with extraordinary economic growth over recent decades in once-poor South Korea, Ireland and China. But the conditions for such growth are getting rarer and rarer, and it may be that this generation is the “very last chance” for countries to get rich. The “main culprit” is fertility rates, which in many places are much lower than expected. In Brazil, for example, the population is 203 million – a long way short of the UN’s recent prediction of 216 million.

This is bad news for economic growth. Rather than reaping a “demographic dividend” from a young population, governments will have to pour resources into caring for the elderly. The taxes needed to do so will further disincentivise young people to have children, creating a vicious cycle. Falling populations will produce “fewer inventors and entrepreneurs”, and fewer powerful companies – Toyota, for example, became a global giant in part because it could refine its product on Japan’s large population. Rich countries have their own problems with fertility rates, which they are likely to fix by taking in more working-age immigrants from poor countries – exacerbating the problem for the latter. It’s already the case that, unlike in the 1990s, poor countries are not growing faster than wealthy ones. That “era of radical transformation” could be behind us.

Inside politics

Grant Shapps and Rishi Sunak. Wiktor Szymanowicz/Future Publishing/Getty

Rishi Sunak’s “political death” is widely predicted, come the election, says Simon Heffer in The New Statesman. No one could deny that the PM has been an improvement on his appalling predecessors Boris Johnson and Liz Truss, a pair that history may come to see as the “two worst British prime ministers”. But he has been hobbled by the “unsure” way he has gone about clearing up after them. Just look at his cabinet appointments. There’s Home Secretary James “not-so-Cleverly”, whose repeated blunders – most recently joking that he drugged his wife – suggest he is ill-suited to a great office of state. Then there’s Defence Secretary Grant Shapps, a man who, a dismayed colleague told me, “will do anything he is asked” because “it doesn’t occur to him that he might not be up to it”. Explaining Tory under-performance at a party before Christmas, a minister told me: “Rishi isn’t a politician. He’s a manager.” And not a very good one at that.

Drink

Yours for £2,947 a bottle: the 1961 Château Latour Grand Vin

Britain’s “strategic wine reserves”

Ever since World War One, Britain has maintained “strategic wine reserves”, says Louis Ashworth in the FT. It falls to the Government Wine Committee to handle buying top plonk for occasions when the administration of the day needs something good to serve to high-profile guests. The 32,310-bottle cellar beneath Lancaster House got a boost during World War Two, when wines from the German Embassy were “requisitioned” and added to the stock. But the day-to-day buying is done, with no official budget, by a retired diplomat and four masters of wine.

What’s remarkable is just how good they’ve been at buying wine. As of April 2022, the estimated market value of the cellar was £3.66m, after a total spend of just £804,312. That makes wine “one of the few areas where government procurement creates value for money”. By auction value, the most expensive wine held is the “apparently legendary” £2,947-a-bottle 1961 Château Latour Grand Vin, though online marketplaces put the 1964 Krug Champagne Vintage Brut even higher, at £9,038. And the GWC keep wonderfully diligent notes. Take the Château Margaux 1988, which comes with the following comments: “Keep – 5/93 (1st review). Keep – 9/98 (2nd review). Keep (3rd review). Keep – 6/06 (4th review). Keep – 2/10 (5th review). Use or keep – 7/15. Keep and hope – 5/19.”

Quoted

“The true soldier fights not because he hates what is in front of him, but because he loves what is behind him.”

GK Chesterton